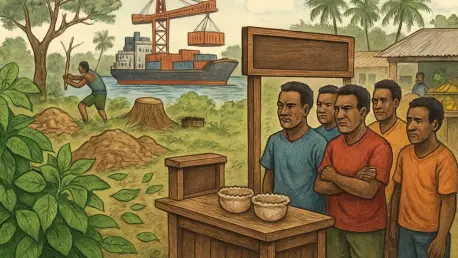

In the bustling capital of Port Vila, where the nightly ritual of drinking kava is deeply woven into the social and cultural fabric, a recent and acute shortage of the cherished root has sent ripples of concern throughout the community. The scarcity, which became particularly pronounced during the high-demand Christmas and New Year holiday period, revealed a complex web of vulnerabilities within the kava supply chain. This was not a simple case of a poor harvest; instead, it was the result of a perfect storm involving seasonal migration, deep-seated logistical hurdles, shifting economic incentives for farmers, and fundamental agricultural limitations. The situation has highlighted the precarious balance between the capital’s unceasing demand and the intricate challenges of sourcing kava from the remote outer islands, prompting a deeper examination of the long-term sustainability of this vital cultural and economic commodity. Key figures, including Chief Theodore Damana, President of the Port Vila Council of Chiefs, have pointed to a convergence of factors that require more than just a temporary fix.

The Human and Agricultural Equation

A significant and immediate contributor to the supply disruption was the annual holiday exodus, a phenomenon that directly impacted the final stage of distribution within the capital. Many of the kava sellers who operate the city’s numerous bars and markets are originally from the outer islands, and they traditionally return home to celebrate the festive season with their families. This mass departure created a sudden vacuum in the retail sector, with fewer vendors available to process and sell the kava that did manage to arrive in Port Vila. This human element was compounded by an unchangeable agricultural reality: kava is not a crop that can be rapidly cultivated to meet short-term demand spikes. With a maturation period ranging from two-and-a-half to four years, farmers are unable to simply plant more and harvest sooner in response to market signals. This inherent inelasticity in supply means that any disruption, whether from human factors or logistical failures, cannot be quickly rectified by increasing production, leaving the market highly susceptible to shortages.

The economic landscape for kava farmers has also undergone a significant transformation, creating new incentives that divert the product away from the capital’s fresh kava market. In the northern islands of Santo, Malekula, and Pentecost, which serve as the primary sources for Port Vila, the market price for dried kava has seen a notable increase. This development has presented farmers with a more lucrative and less arduous alternative to supplying the capital. Instead of undertaking the difficult and costly process of transporting heavy, perishable green kava to port, farmers can now sun-dry their harvest and sell it locally for a higher profit. This shift makes perfect economic sense for individual producers, who can maximize their earnings while avoiding the logistical headaches associated with the urban supply chain. However, the collective impact of these individual decisions has been a substantial reduction in the volume of fresh green kava available for shipment to Port Vila, directly contributing to the scarcity experienced by urban consumers and vendors. This change in market dynamics represents a fundamental challenge to the traditional flow of goods.

Logistical Hurdles and Infrastructural Deficiencies

One of the most persistent and formidable barriers to a consistent kava supply is the stark reality of inadequate infrastructure connecting the remote growing regions to urban centers. The highest quality kava thrives in the volcanic, hilly interiors of the northern islands, areas often situated far from accessible roads or reliable coastal access. For farmers in these regions, the process of transporting their harvested green kava is a monumental task. They must often carry heavy sacks of the root over long distances on foot, navigating difficult terrain to reach a road or a point where a vehicle can collect it. The poor condition of these rural roads further complicates transport, increasing both the time and the cost required to get the product to a wharf for shipping. This “first mile” problem represents a critical bottleneck in the supply chain, as the sheer difficulty and expense of moving the product from farm to port can deter farmers and limit the total volume that can be realistically brought to market, regardless of how much is actually grown.

The shortage in Port Vila was further intensified by the failure of a potential local supply buffer and the inadequacy of short-term relief efforts. Typically, agricultural producers in the more accessible rural areas of Efate, the island where Port Vila is located, might have been able to compensate for a shortfall from the northern islands. However, it was found that local farmers had not planted a sufficient quantity of kava to fill the significant gap in supply. This left the capital almost entirely dependent on the long and fragile supply chain from the north. In an attempt to alleviate the crisis, some measures were taken, including chartering flights from South Pentecost to bring kava directly to the city. While well-intentioned, these efforts proved to be a mere drop in the ocean. The flights, carrying between 200 and 400 kilograms at a time, delivered a supply that was consumed in less than a week, demonstrating that such costly and small-scale interventions are unsustainable and insufficient to meet the city’s consistent, high-volume demand.

Market Responses and a Path Forward

In the face of dwindling supplies, the market in Port Vila responded with significant price volatility, creating a challenging environment for both consumers and the small business owners who depend on kava for their livelihood. As scarcity took hold, the wholesale price of kava in many markets escalated sharply, climbing to as high as VT1,500 per kilogram. This price hike reflected the basic economic principle of supply and demand, but it threatened the viability of many small-scale kava resellers. However, not all market owners followed this trend. Chief Theodore Damana, at his prominent Kava Dock market, made a conscious decision to hold his price steady at VT1,000 per kilogram. He explained this strategy as a measure to protect his regular customers, many of whom operate small businesses selling kava juice. For them, a sudden increase in the wholesale cost would have been devastating, making it impossible to maintain their own prices and potentially forcing them out of business. This decision highlighted a deeper community-oriented perspective within the kava trade, balancing profit motives against the need to maintain the economic stability of the entire ecosystem.

The recent crisis ultimately solidified a consensus among stakeholders that sustainable, long-term solutions were imperative to prevent future shortages. The focus shifted from reactive, short-term fixes to a more comprehensive strategy aimed at strengthening the entire supply chain from the ground up. Key among the proposed solutions was a concerted effort to encourage increased kava planting across the islands, which would build a more robust and diverse supply base capable of weathering disruptions. Alongside this agricultural initiative, it was widely acknowledged that significant investment in rural infrastructure was non-negotiable. Improving the network of roads in the remote growing regions was identified as the most critical step to ease the immense transportation burden on farmers. Finally, establishing more reliable, frequent, and affordable shipping links between the outer islands and Port Vila was seen as essential to ensure a consistent and predictable flow of kava. These strategic actions were viewed as the necessary foundation for securing the future of this culturally and economically vital industry.